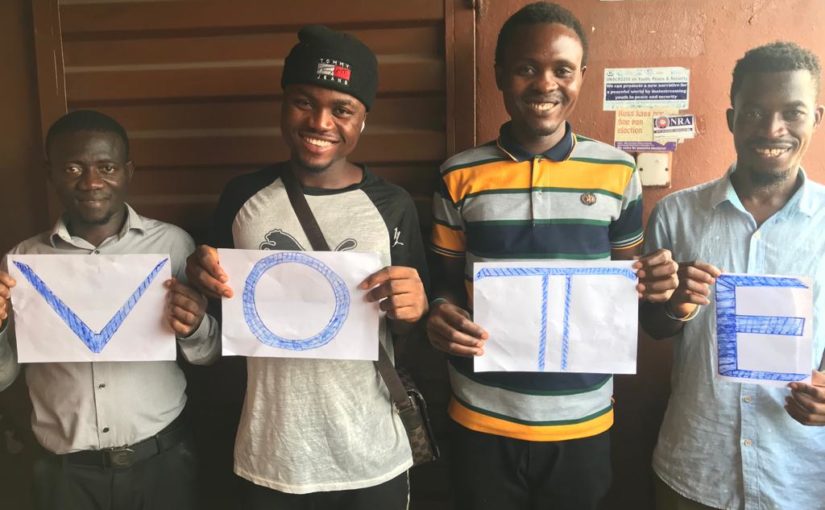

“Peace Na di Answer”, “Peace Fↄ Dae”, or “Election Peace Campaign”.

Social media campaigns like this have mainly been initiated through youth groups, e.g. the Patriotic Advocacy Network Sierra Leone (PAN SL) or the West African Youth Network (WAYN), with the aim to promote peaceful 2023 elections in Sierra Leone. The online implementations for days, weeks and months show that young people are concerned about peace before, during and after elections. Indeed, young people have reason to be worried as the impending presidential and legislative elections are fraught with uncertainty about whether the transition will be peaceful or violent (WANEP 2023).

The factors influencing the electoral process are diverse, interrelated and rooted in the ethical and historical background of Sierra Leone. In the following, I will elaborate on three main factors which are decisive for the development of the electoral process.

The first factor refers to the current economic situation, as costs of living rise daily due to inflation and reliance on imported commodities. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have exacerbated this issue and contributed to a sharp increase in unemployment. Consequently, people are struggling for survival day by day. And the abuse of drugs, especially “Kush” (a mixture of plant sprayed with changing synthetical chemicals, BBC 2022), has increased enormously. The challenging economic situation of most youths makes it easy for politicians to instrumentalise them to orchestrate violence during elections by giving out drugs or money. The economic condition is one baseline determinant that will considerably impact the election process. Thus, fuel scarcity or a continuous increase in food prices could narrow the chances of the current president being re-elected and create a tensed situation which could fuel violent incidents during the election period (World Bank 2023).

Another aspect influencing the election process will be the continued development of the political discourse, offline and online. Currently, the two main political parties, namely SLPP and APC, and their supporters try to dominate the open discourse using tarnishing vocabularies. The current government is trying to frame opponents and protesters as “terrorists” (Bio 2022), while the opposition is trying to frame itself as an unfairly treated victim (Kamara 2023). As the parties have just released their manifestos in the week of 24 May 2023, public discourse has followed this trend of framing. It focuses more on the traditional ethical divide between the parties than on political ideas or content. By doing so, tribal stereotypes are reinforced. And political decisions seem to be based on ethnicity. This is also seen as a general nationwide trend (Lavali & M’Cormack-Hale 2023): Such framing and biased discourse can be compelling, as the August 10 protests in 2022 have proven, in which case “Adebayor”, an expatriate of Sierra Leone, used his influence on social media to motivate young people to protest against the government. Unfortunately, the protests resulted in violence and deaths (Hashim 2023). In conclusion, it is evident that online and offline discourses significantly influence the development of the current situation in Sierra Leone, as politicians and political supporters purposefully use it to fuel peace or violence.

Lastly, the electoral period will be influenced by citizens’ lack of trust in the government and electoral processes in general. A majority of citizens are convinced that the government in power is not controlled and somehow has the freedom to do what they want. This conviction is supported by numerous actions of the current government, such as suspending an audit report on expenditures during their rule or the highly criticised population census (Siegle & Cook 2023, Bangura 2023). This underlines the impression to the general public that the government is allowed to do anything. Additionally, the electoral system was changed to a proportional representation system, which will be applied for the first time in the history of Sierra Leone. Due to a lack of resources and time, the system was not sufficiently explained to its citizens. Because they do not fully comprehend it, the question of whether they will be able to vote correctly and accept the results of the elections remains unanswered (Kamara 2022). Overall, the people lack trust in the electoral system, which may significantly impact the election process (Thomas 2023).

In conclusion, the described factors will have a major impact on the result of the Sierra Leonean elections. Even if everybody hopes for a peaceful process, citizens, politicians, and institutions need to do their best to consider these factors and avoid triggering points for violence. One step taken towards minimising the risk of violence is the ban on public rallies on the street, which are seen as increasing the divide in the population and the tendency to instrumentalise youth as perpetrators of violence (PPRC 2023). That is the first step taken, but still, everybody needs to work hard on a peaceful process.

Bibliography

- APC – All People’s Congress (2023): One Nation Manifesto: Our Collective Agenda for Better Lives and Sustainable Development, May 29, 2023, available at: https://votesamurakamara.com/manifesto (last access: 18 June 2023).

- BBC (2022): Kush: Into the Mad World, February 2022 available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6MPV9zBXYg, (last access: 18 June 2023).

- Bangura, Yusuf (2023): Sierra Leone’s Voter Registration Data Discredits the Midterm Census Data: What are the Implications for the Presidential Election of June 2023, CODESRIA Bulletin Online, No. 6, May 2023, available at: https://journals.codesria.org/index.php/codesriabulletin/article/view/4717 (last access: 16 June 2023).

- Bio, Dr. Julius Maada (2022): August 10 Tragedy: President Bio Addresses the Nation, August 13, 2022, Salone News, The Patriotic Vanguard, available at: http://www.thepatrioticvanguard.com/august-10-tragedy-president-bio-addresses-the-nation (last access: 16 June 2023).

- Hashim, Ibrahim (2023): August Protests Report: Special Investigation Committee Implicates Adebayor, April 14, 2023, Sierra Loaded, available at: https://sierraloaded.sl/news/committee-implicates-adebayor/ (last access: 16 June 2023).

- Kamara, Morlai Ibrahim (2023): APC National-Secretary General, Lansana Dumbuya Allegedly Beaten in Freetown, February 22, 2023, Sierra Loaded, available at: https://sierraloaded.sl/news/apc-lansana-dumbuya-allegedly-beaten-freetown/ (last access: 16 June 2023).

- Kamara, Mabinty M. (2022): Fix the Structures, Not the Electoral System – Lawyer Chides at Sierra Leone PR System, July 13, 2022, Politico SL, available at: https://politicosl.com/articles/fix-structures-not-electoral-system-%E2%80%93-lawyer-chides-sierra-leone-pr-system (last access: 16 June 2023).

- Lavali, Andrew & M’Cormack-Hale, Fredline (2023): Ahead of Election, Should Sierra Leoneans Be Worried About Social Cohesion?, Afrobarometer Dispatch, No. 619, March 23, 2023, available at: https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/AD619-Ahead-of-election-should-Sierra-Leoneans-be-worried-about-social-cohesion-Afrobarometer-23march23-1.pdf (last access: 16 June 2023).

- SLPP – Sierra Leone People’s Party (2023): The New Direction: Consolidating Gains and Accelerating Transformation, People’s Manifesto 2023, May 24, 2023, The Sierra Leone Telegraph, available at: https://www.thesierraleonetelegraph.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/SLPP-New-Direction-Manifesto-2023.pdf (last access: 18 June 2023).

- Thomas, Abdul Rashid (2023): The Road to 2023 Elections in Sierra Leone: A Focus on the Main Actors – Op ed, April 20, 2023, The Sierra Leone Telegraph, available at: https://www.thesierraleonetelegraph.com/the-road-to-2023-elections-in-sierra-leone-a-focus-on-the-main-actors-op-ed/ (last access: 16 June 2023).

- WANEP – West Africa Network for Peacebuilding (2023): WARM Policy Brief, May 2023, Sierra Leone’s 2023 General Elections: Challenges and Opportunities for Democratic Consolidation, available at: https://wanep.org/wanep/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Sierra-Leone-PB5.pdf (last access: 16 June 2023).

- WAYN – West African Youth Network: Peaceful Election Campaign, Facebook, available at: https://www.facebook.com/West-African-Youth-Network-Sierra-Leone-1488345504644114 (last access: 16 June 2023).

- World Bank (2023): The World Bank in Sierra Leone, available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/sierraleone/overview#:~:text=Recent%20Developments%3A%20During%202021%2C%20the,average%20of%2012%25%20during%202021 (last access: 16 June 2023).

- Siegle, Joseph & Cook, Candace (2023): Africa’s 2023 Elections: Democratic Resiliency in the Face of Trials, June 2, 2023, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, available at: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/elections-2023-nigeria-sierra-leone-zimbabwe-gabon-liberia-madagascar-drc/ (last access: 16 June 2023).

- PAN – Patriotic Advocacy Network: Building a Nation Campaign, Facebook, available at: https://www.facebook.com/PatrioticAdvocacyNetwork (last access: 16 June 2023).

- PPRC – Political Parties Regulation Commission (2023): Statement by the PPRC from 28th March 2023, Twitter, available at: https://twitter.com/PPRC_SL/status/1640765474735620097 (last access: 16 June 2023).

(Hinweis: Der vorliegende Blog-Beitrag gibt nicht zwingend die Meinung des KFIBS e. V. wieder.)

(Bildnachweis für das obere Beitragsbild: Mitglieder des West African Youth Network [WAYN], die zur Wahl auffordern; WAYN-Website abrufbar unter: https://www.waynyouth.org/)

Bild:

Straßenwahlkampf von Unterstützern für Dr. Samura Kamara (APC)

Another creative way to tackle the challenges was found by Kolping Veracruz, an organisation that is part of the

Another creative way to tackle the challenges was found by Kolping Veracruz, an organisation that is part of the  Also pastoralist communities and communities in rural settings are suffering from the lack of food supply at local markets in Kenya. Therefore, the organisation

Also pastoralist communities and communities in rural settings are suffering from the lack of food supply at local markets in Kenya. Therefore, the organisation  With the aim for cleaner cities and disinfect streets to fight the virus, there are also other positive effects: In bigger cities in Ghana, gutters are very narrow and full of plastics that hinder water from flowing. This makes a perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes that could then increasingly spread malaria. In the course of fighting the coronavirus, a lot of gutters have been cleaned by the city authorities in Accra, the capital of Ghana, which has helped significantly in decreasing malaria infections. Gabriel Kumalebo states: “From my personal viewpoint, I think because of the coronavirus, cleanliness is ensured in recent times because the environment is clean and we no longer experience stuff like malaria.”

With the aim for cleaner cities and disinfect streets to fight the virus, there are also other positive effects: In bigger cities in Ghana, gutters are very narrow and full of plastics that hinder water from flowing. This makes a perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes that could then increasingly spread malaria. In the course of fighting the coronavirus, a lot of gutters have been cleaned by the city authorities in Accra, the capital of Ghana, which has helped significantly in decreasing malaria infections. Gabriel Kumalebo states: “From my personal viewpoint, I think because of the coronavirus, cleanliness is ensured in recent times because the environment is clean and we no longer experience stuff like malaria.”

Leah Mushi, a journalist from Tanzania, describes how “increased pressure for working women to deliver at work and again to fulfill […] duties at home […] can cause stress and anxiety”. In her view “men don’t do the same […], some help their families but again, they are not expected to do it every day”. Mwansa Mungela from Zambia, on the other hand, shares how similar pressure can be felt as a man.

Leah Mushi, a journalist from Tanzania, describes how “increased pressure for working women to deliver at work and again to fulfill […] duties at home […] can cause stress and anxiety”. In her view “men don’t do the same […], some help their families but again, they are not expected to do it every day”. Mwansa Mungela from Zambia, on the other hand, shares how similar pressure can be felt as a man. “For Zambia […], men are culturally considered to be stronger than women. Hence during the days of quarantine, men have largely been expected to go out and do the shopping or any other tasks outside the home […]. One cashier in Shoprite [a big chain store company] told me that during the days of quarantine it is men who were seen shopping more.” – Mwansa Mungela, Zambia

“For Zambia […], men are culturally considered to be stronger than women. Hence during the days of quarantine, men have largely been expected to go out and do the shopping or any other tasks outside the home […]. One cashier in Shoprite [a big chain store company] told me that during the days of quarantine it is men who were seen shopping more.” – Mwansa Mungela, Zambia To that Percival Quina from South Africa adds: “In rural communities so many households are run by women. They are the breadwinners of the family. The socio-economic impact of COVID-19 is devastating to these female-run households.” He states: “Last week [19th April 2020] I saw an interesting statistic released by the National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD) that 54.7% of the infected are female (male – 44.8%). […] Although this isn’t a big difference, it is quite interesting given that so many women in South Africa perform home-based care work.” – Percival Quina, South Africa

To that Percival Quina from South Africa adds: “In rural communities so many households are run by women. They are the breadwinners of the family. The socio-economic impact of COVID-19 is devastating to these female-run households.” He states: “Last week [19th April 2020] I saw an interesting statistic released by the National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD) that 54.7% of the infected are female (male – 44.8%). […] Although this isn’t a big difference, it is quite interesting given that so many women in South Africa perform home-based care work.” – Percival Quina, South Africa