The unprecedented scenario of the current pandemic has unmasked vulnerabilities in any country of the world as its consequences are overpassing by far a health emergency. Fragile societies that had been struggling with an inner crisis before the outbreak of COVID-19 are particularly affected and face the risk of a longer lasting democratic and human rights backsliding. The Nicaraguan trajectory reflects this pattern in an alarming way, as in the Central American country the pandemic not only led to a struggle for health. The lack of responsible and democratic leadership and a previous humanitarian emergency converge into a de facto state of exception. In this aggravating context with serious institutional deteriorations, it is increased civic engagement that fosters renewed resources of deliberative participation and crisis management.

The Nicaraguan Answers to the Outbreak of the Coronavirus Pandemic

While emergency strategies have been implemented in most Latin American countries, the Nicaraguan government chose its own path. President Daniel Ortega has not taken up any exceptional power. After the first case of COVID-19 had been noticed in the country in March 2020, the president had been vanished for more than a month before appearing again on April 15 in a TV speech. At the same time, Daniel Ortega’s wife and Vice President Rosario Murillo focused on staging social cohesion and solidarity by calling on to march for “Love in Times of Corona”. Tourism was promoted throughout Easter, sports and music events took place, and even the usage of masks was prohibited temporally to impede panic to rise, as monitored by the Nicaraguan Center for Human Rights. Albeit some measures of contention as the control of borders and the attention to the uninsured had been realized meanwhile, no further comprehensive responses were formulated.

Risking a Collapse of the Health Service

Facing not only the lack of governmental measures but also an alarming situation of the health system, already in late April 2020 a pronouncement on the COVID-19 pandemic in Nicaragua was signed by more than 600 Nicaraguan health professionals who urged the government to take up a national health plan. By the end of May 2020, the government published a White Paper to defend the absence of governmental response by arguing the national plan was comparable to the Swedish model of non-isolation and orientated towards the needs of the Nicaraguan nation by fulfilling “balance between the pandemic and the economy”. No comments were made on the fragile context. Only some days later, in early June 2020, the collapse of the health system was declared by at least 34 Nicaraguan medical organizations. The respective statement also warned of an unstoppable tide of infections and once again drew attention to the ill-equipped medical community and a dramatically low health system capacity with only around nine hospital beds available per 10.000 people. The figures on cases up to now highly depend on the respective source. By December 30, 2021, comparative considerations suggest that the Nicaraguan Health Ministry confirmed 6.046 cases and 165 deaths, while the Nicaraguan civil society monitored 11.993 accumulated infections and 2.862 deaths. The latter data includes cases of pneumonia deaths and hence COVID-19 suspected victims which are claimed to be hidden in governmental statistics. It follows that “the absence of Information, prevention and medical care with respect to the COVID-19 crisis in Nicaragua” can be considered a “failure of the State of Nicaragua to comply with its obligation under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights to respect, protect and fulfill the rights to health and life, among other rights, in the face of the COVID-19 crisis” as it was claimed jointly by Nicaraguan and international civil society actors in August 2020.

Humanitarian Emergency in the Context of Democratic Deficits

The impact of the pandemic anyhow surpasses the crisis in the health sector and aggravates a previously existing political and humanitarian crisis. Back in April 2018, social protests against the increasingly authoritarian government had been met by the latter with massive repression and state violence. Though peace talks, which included all sectors of society, the left-wing populist incumbent Daniel Ortega strategically eliminated possible pathways and sources for a return to democratic normalcy. Since then, a human rights crisis has persisted and transformed into a de facto state of exception based on a sophisticated and systematic repression of society as it was denounced by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. There is a clear lack of the rule of law and accountability; independent media is highly restricted, transparency of government measures is not given; political opponents were prisoned, and arbitrary dismissals shrink the numbers of independent professionals in the areas of health and education. Finally, checks and balances are considerably weak and cannot counteract populist presidentialism in the country. As such Ortega’s forenamed undeclared and therefore illegal, temporal leave was not considered at all in the National Assembly. Furthermore, in the shadows of the current emergency, wide-ranging adaptions in the legal framework – before all the passing of a trio of punitive laws and a law on amnesty – have been taken to further shrink space for democratic and civic participation.

Renewed Civic Engagement and Unity in Alliances

At the same time, both the crisis in 2018 and the current health emergency have created new partnerships between distinct national actors. An example of such is given by the Civic Alliance for Justice and Democracy, which evolved in 2018 as one voice of civil society subsuming diverse movements. It currently calls on the Nicaraguan people to pressure the government for change and lists necessary measures in detail. The Observatorio Ciudadano COVID-19 Nicaragua was set up as an independent source of information on the pandemic and prominently claims respect for the rights to health and life. Furthermore, a working group between leading socio-economic institutions, chambers of commerce and the Superior Council of Private Enterprise (COSEP) was integrated, inter alia with the aim to provide a governmentally independent fund for the most vulnerable groups in society. In a context of considerable human rights violations, deep structural deficiencies and lacking accountable political leadership, such rising civil society initiatives have the capacity to answer to the current crisis but also to address a democratic vacuum that undoubtedly has been persisting in Nicaragua throughout the last years.

As such, Nicaragua depicts a scenario in which COVID-19 exposes a vulnerable society to immensely high risks due to the lack of comprehensive governmental measures, of democratic ruling and of the respect for human rights. In this context, the rise of new alliances and civil society engagement demonstrates the considerable accumulation of renewed deliberative and democratic efforts that are aware of the potential long-term and multilayered impacts of the current crisis.

(Hinweis: Der vorliegende Blog-Beitrag gibt nicht zwingend die Meinung des KFIBS e. V. wieder.)

(Bildnachweis für Beitragsbild: Photo by Fusion Medical Animation on Unsplash)

Pictures:

Both pictures were taken by Alina M. Ripplinger.

Another creative way to tackle the challenges was found by Kolping Veracruz, an organisation that is part of the

Another creative way to tackle the challenges was found by Kolping Veracruz, an organisation that is part of the  Also pastoralist communities and communities in rural settings are suffering from the lack of food supply at local markets in Kenya. Therefore, the organisation

Also pastoralist communities and communities in rural settings are suffering from the lack of food supply at local markets in Kenya. Therefore, the organisation  With the aim for cleaner cities and disinfect streets to fight the virus, there are also other positive effects: In bigger cities in Ghana, gutters are very narrow and full of plastics that hinder water from flowing. This makes a perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes that could then increasingly spread malaria. In the course of fighting the coronavirus, a lot of gutters have been cleaned by the city authorities in Accra, the capital of Ghana, which has helped significantly in decreasing malaria infections. Gabriel Kumalebo states: “From my personal viewpoint, I think because of the coronavirus, cleanliness is ensured in recent times because the environment is clean and we no longer experience stuff like malaria.”

With the aim for cleaner cities and disinfect streets to fight the virus, there are also other positive effects: In bigger cities in Ghana, gutters are very narrow and full of plastics that hinder water from flowing. This makes a perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes that could then increasingly spread malaria. In the course of fighting the coronavirus, a lot of gutters have been cleaned by the city authorities in Accra, the capital of Ghana, which has helped significantly in decreasing malaria infections. Gabriel Kumalebo states: “From my personal viewpoint, I think because of the coronavirus, cleanliness is ensured in recent times because the environment is clean and we no longer experience stuff like malaria.”

Leah Mushi, a journalist from Tanzania, describes how “increased pressure for working women to deliver at work and again to fulfill […] duties at home […] can cause stress and anxiety”. In her view “men don’t do the same […], some help their families but again, they are not expected to do it every day”. Mwansa Mungela from Zambia, on the other hand, shares how similar pressure can be felt as a man.

Leah Mushi, a journalist from Tanzania, describes how “increased pressure for working women to deliver at work and again to fulfill […] duties at home […] can cause stress and anxiety”. In her view “men don’t do the same […], some help their families but again, they are not expected to do it every day”. Mwansa Mungela from Zambia, on the other hand, shares how similar pressure can be felt as a man. “For Zambia […], men are culturally considered to be stronger than women. Hence during the days of quarantine, men have largely been expected to go out and do the shopping or any other tasks outside the home […]. One cashier in Shoprite [a big chain store company] told me that during the days of quarantine it is men who were seen shopping more.” – Mwansa Mungela, Zambia

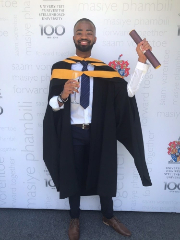

“For Zambia […], men are culturally considered to be stronger than women. Hence during the days of quarantine, men have largely been expected to go out and do the shopping or any other tasks outside the home […]. One cashier in Shoprite [a big chain store company] told me that during the days of quarantine it is men who were seen shopping more.” – Mwansa Mungela, Zambia To that Percival Quina from South Africa adds: “In rural communities so many households are run by women. They are the breadwinners of the family. The socio-economic impact of COVID-19 is devastating to these female-run households.” He states: “Last week [19th April 2020] I saw an interesting statistic released by the National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD) that 54.7% of the infected are female (male – 44.8%). […] Although this isn’t a big difference, it is quite interesting given that so many women in South Africa perform home-based care work.” – Percival Quina, South Africa

To that Percival Quina from South Africa adds: “In rural communities so many households are run by women. They are the breadwinners of the family. The socio-economic impact of COVID-19 is devastating to these female-run households.” He states: “Last week [19th April 2020] I saw an interesting statistic released by the National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD) that 54.7% of the infected are female (male – 44.8%). […] Although this isn’t a big difference, it is quite interesting given that so many women in South Africa perform home-based care work.” – Percival Quina, South Africa

“I always feel that humanity comes above everything else. It hurts when the Kenyan government shuts down clubs, hotels and other major businesses and leaves millions of the Kenyans jobless and hopeless without food. I just can’t sleep nor eat while someone starves within my watch. That’s why I try to feed those I can reach out for.”

“I always feel that humanity comes above everything else. It hurts when the Kenyan government shuts down clubs, hotels and other major businesses and leaves millions of the Kenyans jobless and hopeless without food. I just can’t sleep nor eat while someone starves within my watch. That’s why I try to feed those I can reach out for.” “I have always wanted to make a change in this world but lacked capacity, or so I thought until I came across the phrase ‘extraordinary things are done by ordinary people who have vision, passion and determination’. I stopped making excuses and started with what I had at my disposal and now we are here with a capacity to feed over 500 people and more per day. Everyone is infected or affected in one way or the other: We are just trying to bridge the gap, we are just trying to strengthen the vulnerable.”

“I have always wanted to make a change in this world but lacked capacity, or so I thought until I came across the phrase ‘extraordinary things are done by ordinary people who have vision, passion and determination’. I stopped making excuses and started with what I had at my disposal and now we are here with a capacity to feed over 500 people and more per day. Everyone is infected or affected in one way or the other: We are just trying to bridge the gap, we are just trying to strengthen the vulnerable.”