(Bildnachweis für das obere Beitragsbild: Photo by Trent Erwin on Unsplash)

- Verantwortlicher für den KFIBS-Blog: Dr. Sascha Arnautović, Redaktionsleiter.

Zu Ihrer Information:

Auf diesem Vereinsblog halten Sie die Mitglieder der KFIBS-Forschungsgruppe „USA/Transatlantische Beziehungen/NATO“ auf dem Laufenden mit Beiträgen zur US-Wahl 2020. Auch die Folgen der letzten US-Wahl werden von den Autorinnen und Autoren der o. g. KFIBS-Forschungsgruppe thematisiert und diskutiert.

Zusätzlich haben wir noch eine vornehmlich sicherheitspolitisch ausgerichtete Themenreihe auf unserem Blog zur globalen Coronavirus-Pandemie aus der Perspektive verschiedener Regionen vorgesehen.

Beide thematischen Blog-Kategorien – sprich: „Die US-Wahl 2020 und ihre Folgen“ sowie „Implikationen der globalen Coronavirus-Pandemie“ – finden Sie ab Mai 2020 unter folgenden Links: https://kfibs.org/category/us-wahl_2020/, https://kfibs.org/category/globale_coronavirus-pandemie/. Eine weitere thematische Blog-Kategorie „Amerika nach der Präsidentschaftswahl 2024 und die Folgen für den Westen“ startet ab Januar 2025 unter folgendem Link: https://kfibs.org/category/amerika-nach-der-praesidentschaftswahl-2024-und-die-folgen-fuer-den-westen/.

Mit einer dritten thematischen Blog-Kategorie „Internationale Beziehungen Afrikas“ der KFIBS-Forschungsgruppe „Afrika“ starten wir ab Juni 2023. Diese kann unter folgendem Link abgerufen werden: https://kfibs.org/category/internationale_beziehungen_afrikas/.

Allgemeine Blog-Themen, die sich nicht den zuvor genannten thematischen Blog-Kategorien zuordnen lassen, finden Sie ab März 2022 im folgenden Seitenabschnitt.

11.12.2024: Der UN-Zukunftsgipfel: Eine neue Agenda für die Herausforderungen unserer Zeit?

Malte Möbius, Lisa Voigt und Dr. Sonja Thielges (Mitglieder der KFIBS-Forschungsgruppe „Globale Zukunftsfragen“, https://kfibs.org/forschungsgruppen/thematische-forschungsgruppen/globale-zukunftsfragen/)

Am 22. und 23. September 2024 fand im Rahmen der UN-Generalversammlung in New York der UN-Zukunftsgipfel („Summit of the Future“) statt. Deutschland spielte dabei gemeinsam mit Namibia als „Co-Facilitator“ eine herausragende Rolle für die Einigung auf die Abschlussdokumente des genannten Gipfels. Die KFIBS-Forschungsgruppe „Globale Zukunftsfragen“ beschäftigt sich mit vielen Themen des Zukunftsgipfels, darunter Klimaschutz, nachhaltige Energiesysteme, künstliche Intelligenz sowie Digitales und Menschenrechte. Wie sind die Gipfeldokumente im Hinblick auf ihren Anspruch aus der Perspektive „unserer“ Themen zu bewerten? Wie ambitioniert sind die erarbeiteten Lösungsvorschläge und wo bestehen möglicherweise weiterhin Lücken? Wir möchten diesen KFIBS-Blogbeitrag dafür nutzen, um einen kritischen Blick auf die Gipfeldokumente zu werfen.

Zur Entstehung der Gipfeldokumente des Summit of the Future

Dem Gipfel ging ein komplexer Prozess voraus, der sich über mehrere Jahre erstreckte: Im Jahr 2020 beauftragten die UN-Mitgliedstaaten den UN-Generalsekretär, eine „gemeinsame Agenda“ für den Umgang mit gegenwärtigen und zukünftigen globalen Herausforderungen zu entwickeln. 2021 legte der UN-Generalsekretär zu diesem Zweck den Bericht „Our Common Agenda“ vor, der auch den Zukunftsgipfel in New York vorschlug. In seiner Vision forderte der UN-Generalsekretär ein multilaterales System, das inklusiv, vernetzt und effektiv sein und der Umsetzung der UN-Nachhaltigkeitsziele (Sustainable Development Goals, kurz: SDGs) einen „Turbo“-Schub verleihen sollte. Der UN-Generalsekretär legte auf Basis des „Our Common Agenda“-Berichts 11 Policy Briefs vor, um die Ideen zu vertiefen.

Auf dem Gipfel im September 2024 nahmen die Staats- und Regierungschefs formell den sogenannten Zukunftspakt („Pact for the Future“) an. Neben dem Pakt verabschiedeten sie einen globalen Digitalpakt, den sogenannten Global Digital Compact, und die „Declaration on Future Generations“.

Der Zukunftspakt in der Gesamtschau: Hohe Ambitionen der Zielsetzungen, wenig Innovation bei der Konkretisierung der Umsetzung

Die Ambitionen des Zukunftspakts sind hoch: Er soll einen Leitfaden bieten für die beschleunigte Umsetzung der Agenda 2030; wichtige Zukunftsthemen für die UN, wie z. B. „künstliche Intelligenz“ und „neue Waffensysteme“, identifizieren; Fragen der Generationengerechtigkeit beleuchten; und schließlich Ideen für die lange geforderte Reform des UN-Systems beinhalten. Der erste Entwurf lag im Januar 2024 vor. Die Verhandlungen waren geprägt von einem zähen Ringen um die Inhalte des Pakts und die damit verbundenen Bestrebungen. Die politischen Differenzen zwischen den UN-Mitgliedstaaten und ihre unterschiedlichen Schwerpunktsetzungen wurden einmal mehr deutlich. Dem ersten Entwurf folgten insgesamt fünf Revisionen. Vorab war vereinbart worden, dass der Pakt im Konsens verabschiedet werden soll.

Der finale Pakt enthält fünf Kapitel – und die bereits genannten zwei weiteren Dokumente im Anhang umfassen den „Globalen Digitalpakt“ sowie die „Erklärung zu zukünftigen Generationen“. Der Pakt beschäftigt sich mit unterschiedlichen Themen von nachhaltiger Entwicklung über digitale Kooperation bis hin zur Transformation der Global Governance.

Im Zukunftspakt werden im Themenfeld „Sozial-, Umwelt- und Transformationspolitik“ einige Lücken im multilateralen System genannt, die für Forschungen im Bereich intertemporaler und ökosozialer Humangerechtigkeit relevant sind, als da wären: Lücken in der auf die Zukunft bezogenen Gerechtigkeit und in der Schaffung von sozialer (Action 6, 7, 8) und ökologischer (Action 9,10) Gerechtigkeit sowie Inklusionsanliegen insgesamt (Action 13) wie auch verstärkte Entwicklungs- und Teilhabemöglichkeiten für Jugendliche (Action 34-37). Dabei werden u. a. Aspekte wie healthy planet (= „gesunder Planet“) und whole-of-society sustaining peace (= „gesamtgesellschaftlich nachhaltiger Frieden“) genannt. Diese markieren gewiss wichtige Zielsetzungen. Die Zielstrebigkeit und Effektivität des multilateralen Systems, das solche Ziele vertritt und durchsetzen will, müsste aber noch deutlich verstärkt werden, damit diese hehren Ziele auch in den untergeordneten Ebenen der Implementierung (z. B. der nationalen oder zivilgesellschaftlichen Ebene) tatsächlich auch erreicht werden können.

Kritisch anzumerken ist, dass der zugrunde liegende Innovationsbegriff in dem betreffenden Dokument sehr technisch orientiert zu sein scheint. Es werden keine Potenziale der (menschenrechtlich-wertebasierten) sozialen Innovativität adressiert, d. h. Innovativität wird nicht auf den sozialen Wandel bezogen, der neben technischen Innovationen als eine wichtige Komponente zur Erreichung der Zielsetzungen betrachtet werden muss. Ebenso lässt sich kritisch anmerken, dass in dem Dokument Mensch-Umwelt-Beziehungen nicht noch stärker in Betracht gezogen werden, wie etwa die existenzielle Abhängigkeit des Menschen von der Natur.

Aus der Perspektive der ökosozialen Innovationsforschung über die Entwicklung von Kulturen, die ein Miteinander im Sinne der Menschenrechte unterstützen und die zur gesellschaftlichen Verwirklichung menschenrechtlicher Grundsätze beitragen, erscheint eine verbesserte Global Governance, u. a. auch digital, durchaus sinnvoll, um diese Ziele politisch „von oben“ (top-down) als Ordnungsrahmen zu implementieren. Sie müssen aber auch „von unten“ (bottom-up) gelebt und verwirklicht werden. Hier könnte der Zukunftspakt stärkere Impulse setzen.

Der Zukunftspakt und die Klimatransformation: Der Status quo als Fortschritt?

Für den Klimaschutz gibt der Pakt auf den ersten Blick Schwung für die multilaterale Klimadiplomatie. Im Dokument verpflichten sich die Staaten, ihre Anstrengungen in Bezug auf ihre Zusagen im Rahmen der UN-Klimarahmenkonvention (UNFCCC) und des Pariser Klimaabkommens zu verstärken. Sie bekennen sich zum Ziel, die globale Erderwärmung auf möglichst 1,5 Grad zu begrenzen, um wenigstens die schlimmsten Klimawandelfolgen zu vermeiden.

Durchaus selbstkritisch wird dabei im Text angemerkt, dass die Fortschritte beim Klimaschutz deutlich zu langsam sind, und die Treibhausgase, anstatt zu sinken, global weiter ansteigen. Die Leidtragenden dessen seien, so betont der Text, vor allem die Entwicklungsländer. Besonders wichtig sei in diesem Zusammenhang, ihnen finanzielle Unterstützung für die Implementierung von Klimaschutz- und Anpassungsmaßnahmen zukommen zu lassen.

So weit, so gut. Wenig innovativ fällt dann aber die Interpretation der notwendigen Maßnahmen und der Governance-Strukturen aus. Auf der UN-Klimakonferenz in Dubai 2023 einigten sich 197 Staaten und die Europäische Union mit dem sogenannten Energiepaket auf Ziele, um den Klimaschutz voranzutreiben, darunter die Verdreifachung der Kapazitäten für erneuerbare Energien auf globaler Ebene bis 2030, die Verdoppelung der Energieeffizienzrate bis 2030 und die Abkehr von fossilen Energieträgern in Energiesystemen. Die Formulierungen aus dem in Dubai vereinbarten „Global Stocktake“ wurden immerhin im Zukunftspakt übernommen. Es werden auch Technologien, welche die Staaten fördern sollten, wie der grüne Wasserstoff oder die „low-carbon“-Treibstoffe berücksichtigt. Eingeschlichen hat sich im Kontrast zu den Ergebnissen der letzten UN-Klimakonferenz eine Formulierung zur wichtigen Rolle sogenannter transitional fuels für die globale Energiewende. Was diese sind, bleibt jedoch unklar. Es ist zu vermuten, dass sich hier Länder durchsetzen konnten, welche die Wichtigkeit von Erdgas als Brücke beim Übergang von fossilen zu erneuerbar-basierten Stromsystemen betonen wollten. Um die Ziele umzusetzen, setzt der Pakt auf das neue internationale Klimafinanzierungsziel, das auf der Klimakonferenz in Baku verhandelt wurde, und die neuen „Nationalen Klimaschutzbeiträge“ (kurz: NDCs), welche die Vertragsstaaten des Pariser Klimaabkommens von 2025 bei der UN einreichen müssen.

Neue Governance-Mechanismen oder Ambitionen, die über das in den vergangenen Jahren ohnehin schon Beschlossene hinausgehen, fehlen in dem Dokument allerdings gänzlich. Der Zukunftspakt betont nicht die Dringlichkeit ambitionierterer Klimaschutzmaßnahmen im Hinblick auf eine lebenswerte Welt für zukünftige Generationen. Das Dokument hat im Klimaschutzbereich daher keinen Transformationscharakter, sondern unterstreicht vielmehr die Wichtigkeit bestehender Prozesse wie die UN-Klimarahmenkonvention. In Zeiten von geopolitischen Krisen, Fake News und Desinformationskampagnen sowie dem Erstarken rechtsextremer und populistischer Kräfte weltweit könnte man dies auch schon als Erfolg verbuchen. Trotz all dieser Herausforderungen hat man sich geschlossen hinter die Ergebnisse der letzten Klimakonferenz gestellt. Einen „Turbo-Schub“ für die Klimaziele bedeutet das aber leider nicht!

Der „Globale Digitalpakt“: Klärung wichtiger Fragen bleibt vorerst Zukunftsmusik

Der ebenfalls beim Zukunftsgipfel beschlossene „Globale Digitalpakt“ (Global Digital Compact, kurz: GDC) ist das Ergebnis eines mehrjährigen Prozesses, der durch den UN-Generalsekretär angestoßen wurde und welcher auf die Stärkung der UN in der internationalen Digitalpolitik abzielt. Der Digitalpakt deckt einen breiten Themenbereich ab: die Überwindung der „digitalen Kluft“ (digital divide), die Förderung und den Schutz der Menschenrechte im digitalen Raum, eine inklusivere Digitalwirtschaft und den Umgang mit internationalen Datenflüssen und internationaler Governance für künstliche Intelligenz (KI). Auch die Verhandlungen um den GDC waren von großen politischen Differenzen geprägt. Neben inhaltlichen Fragen betraf dies auch die grundsätzliche Frage der Rolle der UN in der internationalen Digitalpolitik. Nicht staatliche Stakeholder aus der Zivilgesellschaft, Wissenschaft, technischen Community und der Wirtschaft forderten einen inklusiveren Prozess und kritisierten den Pakt als Versuch einer Machtverschiebung hin zu den Staaten. Andere kritisieren hingegen die Einbeziehung von nicht staatlichen Stakeholdern, insbesondere von Unternehmen.

Der Text durchlief seit der Veröffentlichung des ersten Entwurfs durch die sogenannten Co-Fazilitatoren Sambia und Schweden mehrere Überarbeitungen. Einerseits wurden wichtige Punkte aufgenommen, wie etwa das Bekenntnis zu internationalen Menschenrechtsnormen oder zum Multi-Stakeholder-Modell in der Internet-Governance; andererseits wurde der Text an vielen Stellen leider abgeschwächt. Beispielsweise sahen frühere Versionen die Entwicklung eines globalen Umweltdatensatzes zur Umsetzung des Pariser Abkommens und der UN-Klimarahmenkonvention vor. Zudem enthielt der erste Entwurf konkrete Zielwerte für Konnektivität und digitale Fähigkeiten, die später gestrichen wurden. Auch die Sprache zur Arbeit des Hohen Kommissars der UN für Menschenrechte wurde abgeschwächt. In dem Abschnitt zu KI zielt der Pakt auf eine Stärkung internationaler Governance ab und sieht einen „Global Dialogue on AI Governance“ sowie ein „International Scientific Panel on AI“ nach dem Vorbild des „Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change“ (kurz: IPCC) vor. Andere neue Technologien wie Quanten-Computing und Biotechnologie sind hingegen nicht im Text berücksichtigt. Der „follow-up“-Prozess war in den Verhandlungen besonders umstritten. Viele Fragen über die Ausgestaltung wurden in die Zukunft verlagert. Die nächsten Jahre könnten daher zur Ausarbeitung konkreter Lösungen in inklusiven Prozessen genutzt werden. Gelegenheiten hierzu wären beispielsweise das Review des Weltgipfels für die Informationsgesellschaft 2025, bei dem über die Erneuerung des Mandats des Internet Governance Forum (IGF) entschieden wird, sowie die Ausarbeitung der Modalitäten für das „High-level review of the Global Digital Compact“, welches während der 82. UN-Generalversammlung stattfinden soll.

Fazit: Der Zukunftspakt als möglicher Anstoß für Reformprozesse

Zukunftspakt und Globaler Digitalpakt bilden einen (Minimal-)Konsens unter den UN-Mitgliedern ab, dem zähe Verhandlungen vorausgingen. Bis zum ersten Gipfeltag war unklar, ob angesichts anhaltender politischer Differenzen ein Konsens zustande kommt. Dass der Pakt dann letztlich angenommen wurde, kann als Erfolg bewertet werden. Der Pakt benennt wichtige Zukunftsthemen und enthält auch konkrete Punkte und Prinzipien, wie z. B. die Bekenntnisse zu den Menschenrechten. Der Globale Digitalpakt enthält immerhin an einigen Stellen Ansatzpunkte für verbesserte Koordination, so etwa im Bereich „Konnektivität“. Neue Vorschläge für eine Transformation und ein effektiveres und inklusiveres multilaterales System sind aus der Perspektive der Forschung zu Humangerechtigkeit, zur Klimapolitik und zur Digitalpolitik jedoch kaum in den Dokumenten zu finden. Einige Reformvorschläge, die aus anderen Governance-Kontexten stammen, wie beispielsweise die Besteuerung von „Superreichen“ oder das Independent International Scientific Panel on AI, wurden nun aber immerhin im UN-Kontext konkretisiert. Kleine Erfolge also, aber auch weiterhin große Lücken.

So sollten Zukunftspakt und Globaler Digitalpakt wohl als Basis für weitere Debatten gedeutet werden, z. B. über Inklusivität und die Reform der bestehenden Global Governance-Institutionen. Öffentliche und private Gelder für die Transformation zu mobilisieren, wird dabei entscheidend sein. Wichtig für die Umsetzung wird daher nun die koordinierte Ausgestaltung von „follow-up“-Prozessen unter Beteiligung aller relevanten Akteurinnen und Akteure sein. Denn die größere Effektivität des multilateralen Systems ist absolut zentral, um den Herausforderungen der Zukunft zu begegnen und die Nachhaltigkeitsagenda der UN zum Erfolg zu führen. Auf eigene Faust werden einzelne Staaten oder kleine Gruppen hier keine ausreichenden Erfolge verbuchen können.

(Hinweis: Der vorliegende Blog-Beitrag gibt nicht zwingend die Meinung des KFIBS e. V. wieder.)

(Bildnachweis für Beitragsbild: Foto von Matthew TenBruggencate auf Unsplash)

26.08.2024: Russland und die Migranten aus Zentralasien: Entwicklungsmotor oder Risikofaktor?

Zusammenfassung

Der verheerende Terrorakt im Einkaufszentrum „Crocus City Hall“ durch ethnische Tadschiken nahe Moskau am 22. März 2024 hat große Schockwellen in der russischen Politik und Öffentlichkeit verursacht. Mit über 140 getöteten Zivilisten gilt er als eines der blutigsten Kapitel der modernen russischen Geschichte nach der Geiselnahme von Beslan im Jahr 2004. Einmal mehr sind in der russischen Gesellschaft und in offiziellen Kreisen heftige Debatten darüber entbrannt, ob Russland vor dem Hintergrund dieses Unsicherheitsgefühls eine Erwerbszuwanderung aus Zentralasien überhaupt benötigt. Doch die sich stellende Frage lautet: Tragen die Migranten die alleinige Verantwortung für tödliche Gewaltakte und für die teilweise sehr konfuse Sicherheitslage im Land?

Der folgende KFIBS-Online-Beitrag wirft einen Blick auf die dynamische Entwicklung der Arbeitsmigration aus den ehemaligen Sowjetrepubliken Zentralasiens nach Russland und analysiert die wirtschaftlichen, administrativen und sicherheitspolitischen Implikationen der zumeist fehlgeleiteten russischen Migrationspolitik seit dem Jahr 1991. Genau im staatlichen Handeln hinsichtlich der Migrationsthematik sucht der Autor die Antwort auf die oben genannte Frage.

Die Migrationswelle nach 1991

Der Migrationskorridor zwischen Russland und den Ländern Zentralasiens entstand mit dem Untergang der Sowjetunion. Zwar war die Zuwanderungsrate aus Zentralasien nach Russland bereits in den 1980er-Jahren recht hoch, jedoch kam es zu einer regelrechten Auswanderungswelle erst nach 1991. Allein bis 1994 haben schätzungsweise 2,5 Millionen Menschen aus Usbekistan, Tadschikistan und Kirgisistan ihre Heimat in Richtung Russland verlassen (Abaschin, 2014). Die Art der Migration hat sich jedoch mit der Zeit verändert. In den 1990er-Jahren gab es einen enormen Zustrom sogenannter erzwungener Migration nach Russland aus Ländern mit einer instabilen politischen Lage, in denen entweder gewisse ethnische Volksgruppen verfolgt wurden oder kriegsähnliche Zustände herrschten (exemplarisch sei hier genannt: der Bürgerkrieg in Tadschikistan von 1992 bis 1997). Zur damaligen Zeit handelte es sich bei den meisten Migranten um russischstämmige Menschen, die faktisch in ihre historische und kulturelle Heimat zurückkehrten.

In den zentralasiatischen Republiken führte der Rückgang des Wirtschaftswachstums nach 1991 zu massenhafter Arbeitslosigkeit und zu einem Rückgang des erwerbsfähigen Bevölkerungsanteils. Die Hauptfaktoren, welche die Arbeitsmigration neben den politischen Faktoren begünstigten, waren die schwierige wirtschaftliche Lage, das wachsende Gefälle der Lebensstandards im Vergleich zu anderen Ländern, die unklaren Entwicklungsaussichten sowie das niedrige Niveau der durchschnittlichen Monatslöhne.

Der starke Zulauf von Erwerbstätigen diente als Anlass für die Gründung des Föderalen Migrationsdienstes Russlands zu Beginn des Jahres 1992 und gab den Anstoß zur Konzipierung einer Migrationsgesetzgebung, die den Status und die Rechte von Migranten in gewisser Weise definieren sollte. 1993 wurden die ersten Gesetze „Über Flüchtlinge“ und „Über Zwangsmigration“ verabschiedet. Derzeit ist die Hauptdirektion für Migrationsfragen des Innenministeriums von Russland, die per Erlass von Wladimir Putin am 5. April 2016 geschaffen wurde, für migrationsbezogene Angelegenheiten sowie für die Bekämpfung der illegalen Migration zuständig (Government.ru, 2016).

Erwerbszuwanderung nach Russland – Herausforderungen und Versäumnisse

Die Arbeitsmigration macht derzeit den größten Teil der Migrationsströme nach Russland aus. Gemäß der Föderalen Statistikbehörde Russlands „Rosstat“ kamen die meisten Erwerbszuwanderer im Jahr 2023 aus Usbekistan (1,6 Millionen), gefolgt von Tadschikistan (985.500) und Kirgisistan (516.600). Allein auf diese drei Länder entfielen 87 Prozent aller Personen, die zu Arbeitszwecken nach Russland reisten. Verglichen mit dem Jahr 2019 bedeutet das ein Anstieg von mehr als 30 Prozent. Nicht einmal der Krieg in der Ukraine konnte dieser Wachstumsdynamik einen Abbruch tun (Schukurow, 2023).

Fast zwei Jahrzehnte nach Erlangung der Unabhängigkeit führte die Abnahme der Bevölkerung im erwerbsfähigen Alter zu einer Verschärfung des Arbeitskräftemangels in Russland. Einher ging diese Tendenz mit der wachsenden Arbeitslosigkeit in Zentralasien und der Intensivierung der Zuwanderungswelle. Die Entwicklung der natürlichen Bevölkerungsbewegung und der Altersstruktur in Russland macht den demografischen Faktor zu einem ernsthaften Problem für die sozioökonomische Entwicklung des Landes. Vom demografischen Blickwinkel aus betrachtet, profitiert also Moskau von dieser Arbeitsmigration, da der Zustrom von Migranten bis zu einem gewissen Grad die ständig sinkende Bevölkerungszahl kompensiert. Nach Angaben der Föderalen Statistikbehörde „Rosstat“ ist die jährliche Auffüllung des russischen Arbeitskräftepotenzials durch junge Menschen, die in das erwerbsfähige Alter kommen, zwischen 2000 und 2020 um 40 Prozent zurückgegangen. Infolgedessen schrumpft und altert die Erwerbsbevölkerung: Mehr als die Hälfte der Beschäftigten in der Russischen Föderation ist über 40 Jahre alt. Prognosen zufolge könnte die Anzahl der unbesetzten Stellen durch den Verlust von Arbeitsplätzen in den nächsten zehn Jahren die 5-Millionen-Marke erreichen. Die Belastung der russischen Wirtschaft durch Alterung nimmt in der Folge zu: Der Anteil der Bevölkerung im erwerbsfähigen Alter liegt gegenwärtig bereits bei über 25 Prozent, d. h. jeder vierte Einwohner Russlands gilt als Rentner (Iwachnjuk, 2023). Auf der anderen Seite bietet sich für Staaten wie Usbekistan, Tadschikistan und Kirgisistan, deren Bevölkerung sich seit dem Zusammenbruch der UdSSR verdoppelt hat, mit der Emigration die Möglichkeit, der Überbevölkerung angesichts des akuten Mangels an Arbeitsplätzen vorzubeugen. Schließlich ist die Bevölkerung dieser Länder auf überlebenswichtige Geldtransfers aus Russland angewiesen. Laut dem KNOMAD-Projekt der Weltbank lagen Tadschikistan und Kirgisistan im Jahr 2022 weltweit auf Platz fünf und sechs der Länder mit dem höchsten Anteil von Rücküberweisungen am BIP. Statistischen Daten zufolge hängt das BIP von Kirgisistan zu mehr als 31 Prozent von Transfers aus dem Ausland ab. Für Tadschikistan liegt dieser Anteil sogar bei 32 Prozent. In Usbekistan, dem bevölkerungsreichsten Land Zentralasiens, machen die ausländischen Überweisungen 17 Prozent des gesamten BIP aus (Gusewa, 2023).

Die massenhafte Migration, die über zwei Jahrzehnte größtenteils unkontrolliert vonstatten ging, schuf gleichzeitig Probleme, die bis heute andauern. Viele Arbeitsmigranten halten sich illegal in Russland auf, verfügen nicht über die erforderliche Arbeitserlaubnis und sind nicht offiziell bei den zuständigen Migrationsbehörden registriert. Für die meisten Privatunternehmen stellt dieser Umstand allerdings kein Hindernis dar, die Migranten ohne behördliche Genehmigung zu Niedriglöhnen heimlich zu beschäftigen. Die visafreie Regelung der zentralasiatischen Länder mit Russland, die das Recht auf einen 30-tägigen Aufenthalt in Russland haben, trägt ebenfalls indirekt zur Entstehung der illegalen Migration bei, denn nach Ablauf dieser Frist versuchen die meisten Migranten, auf illegalem Wege dauerhaft in Russland zu bleiben.

Die irreguläre Migration in die Russische Föderation begünstigt zudem eine Disproportionalität, was die Verteilung der Zuwanderer aus Zentralasien auf russischem Territorium angeht. Die größte Konzentration an erwerbsfähigen Ankömmlingen geht auf das Konto der entwickelten Metropolregionen im Westen (sog. Föderationskreis Zentralrusslands um Moskau und Sankt Petersburg herum) und im Süden (Rostow am Don, Wolgograd, Krasnodar etc.) des Landes. Die Regionen wie Sibirien oder Ural gehören hingegen nicht zu den wirklichen Nutznießern der Arbeitsmigration. Neben dem geografischen Aspekt betrifft die disparate Verteilung auch den wirtschaftlichen Aspekt. Über 50 Prozent aller zentralasiatischen Erwerbstätigen arbeiten in der Baubranche, etwa 30 Prozent im Handel, Dienstleistungs- und Industriesektor und der Rest in der Landwirtschaft. Die Popularität der Baugewerbe unter den Migranten ist vor allem auf hohe Nachfrage und bessere Löhne zurückzuführen.

Ein seit Jahren vorherrschendes Thema im russischsprachigen Diskurs stellt die geringe Qualifizierung von Arbeitskräften aus Zentralasien dar. Ein Großteil von ihnen spricht kaum Russisch und verfügt nur über einen sekundären Schulabschluss bzw. in seltenen Fällen über eine mittlere Berufsausbildung. Die zentralasiatischen Arbeitskräfte üben hauptsächlich schwere körperliche Tätigkeiten aus, die bei der russischstämmigen Bevölkerung aufgrund mangelnden Ansehens und der schlechten Bezahlung unbeliebt sind. Die positive Wirkung dieser Tendenz für Russland zeigt sich aber darin, dass der Mangel an Arbeitskräften in gewissen Branchen ausgeglichen, die Produktion am Laufen gehalten und auf diese Weise der Konkurs von Unternehmen verhindert werden können.

Die mit Abstand größte Herausforderung im Zusammenhang mit der unkontrollierten Arbeitsmigration in der Russischen Föderation stellen die sicherheitspolitischen Bedenken dar, die dem russischen Staat zunehmend Kopfzerbrechen bereiten. In der russischen Öffentlichkeit herrscht die weitverbreitete Auffassung, die Erwerbszuwanderer aus Zentralasien trügen die Hauptverantwortung für die Zuspitzung der Sicherheitslage im Land. Die blutigen Bombenanschläge auf einen Wohnkomplex in Moskau im Jahr 1999, das tödliche Geiseldrama im Moskauer Dubrowka-Theater von 2002 und die Geiselnahme im nordossetischen Beslan im Jahr 2004 forderten Hunderte Menschenleben und hinterließen tiefe Spuren im kollektiven Bewusstsein. Stereotypen, Vorurteile und eine ablehnende Haltung gegenüber den Migranten sind seitdem zu beobachten. Nach einer relativ ruhigen Phase in den Folgejahren sprengte sich am 3. April 2017 ein usbekisch-stämmiger Kirgise in der St. Petersburger U-Bahn in die Luft und riss 16 Menschen in den Tod. Dies hat die migrationsfeindliche Stimmung in Russland erneut verschärft. Laut einer Umfrage des Meinungsforschungsinstituts „Lewada-Zentrum“ vom Januar 2022 gaben nur 20 Prozent der befragten Russen an, sie würden die Einwanderer aus Zentralasien als Mitbürger akzeptieren. Sieben Prozent würden die Tadschiken und Usbeken als Nachbarn und nur fünf Prozent als Arbeitskollegen ansehen (Current Time, 2022).

Der illegale und unrechtmäßige Zustrom nach Russland spielt auf der anderen Seite den radikalen Islamisten aus Zentralasien in die Hände. Die rigorosen Maßnahmen in Usbekistan, Kirgisistan und Tadschikistan, die ihre Gesetzgebung im Kampf gegen die extremistischen Strömungen verschärft haben, treiben immer mehr religiöse Fundamentalisten zur Flucht nach Russland, wo sie meist in den Untergrund gehen und dort ihr Unwesen treiben. Mehr als zwei Jahrzehnte hat der russische Staat mit seiner inkohärenten, lückenhaften und von der Korruption überschatteten Migrationspolitik dieser sicherheitsgefährdenden Tendenz tatenlos zugeschaut. Die russische Wirtschaft, die seit vielen Jahren von billigen Arbeitsmigranten profitiert, hat auf der anderen Seite kaum in die dauerhafte Integration von Zuwanderern in den russischen Arbeitsmarkt investiert. Die Herausbildung geschlossener Gemeinschaften ist die Folge, die wiederum unvermeidlich zu einem Anstieg der Kriminalität und zur Erhöhung der Terrorgefahr führt. Auch wenn sich die russische Führung voreilig auf die Ukraine als Drahtzieher des jüngsten Terroranschlags im „Crocus City Hall“ berufen hat, sprechen konkrete Anhaltspunkte dafür, dass eine islamistische Urheberschaft in Wirklichkeit dahintersteckt. Die festgenommenen tadschikischen Staatsbürger, die diesen Terrorakt unmittelbar verübt haben sollen, dürften ihre Pläne wohl in einer der Parallelgesellschaften geschmiedet haben.

Fazit

Seit nunmehr über 30 Jahren gehören die Arbeitsmigranten aus Zentralasien zur Realität Russlands, die in vielerlei Hinsicht als Entwicklungsgarant der russischen Wirtschaft dienen. Ohne Zuwanderung aus diesen Ex-Sowjetrepubliken wäre die ökonomische Wettbewerbsfähigkeit bei gleichbleibender bzw. sinkender Erwerbsbeteiligung ernsthaft gefährdet. Der seit zweieinhalb Jahren andauernde Angriffskrieg Russlands gegen die Ukraine, der bereits den Verlust vieler qualifizierter Arbeitskräfte zur Folge hat, zeichnet langfristig düstere Aussichten für die ohnehin abgeschwächte Ökonomie Russlands und macht die Herbeischaffung von ausländischen Erwerbstätigen unter den gegenwärtigen Umstanden erforderlicher denn je.

Die Regulierung der Erwerbsmigration und die Einhaltung der gesetzlich festgelegten Richtlinien durch Ankömmlinge und Arbeitgeber sind jedoch nach wie vor die Achillesferse der russischen Migrationspolitik. Die häufigen Diskussionen über die Migrationskrise sind in erster Linie der Konzeptlosigkeit und der fehlenden Konstanz geschuldet, was sowohl die russischen Bürger als auch die Zuwanderer selbst stark verunsichern dürfte. Infolgedessen entwickelt sich die Migration zu einem destabilisierenden Faktor, vor allem wenn bei aufenthaltsrechtlichen Angelegenheiten nicht die staatlichen Integrationsstrukturen, sondern vielmehr Parallelgesellschaften und im Untergrund agierende ethnische Organisationen das Sagen haben. Nicht die Arbeitsmigranten an sich stellen insofern die eigentliche Gefahrenquelle für Russland dar. Vielmehr ist es die unangemessene und fahrlässige Handhabung der Migrationsthematik durch staatliche Instanzen, welche die Sicherheitslage im Land bewusst einem Risiko aussetzen und in der russischen Gesellschaft für Verunsicherung sorgen.

(Hinweis: Der vorliegende Blog-Beitrag gibt nicht zwingend die Meinung des KFIBS e. V. wieder.)

(Bildnachweis für Beitragsbild: https://oxu.az/ru/v-mire/mvd-rossii-predlozhilo-vydvoryat-migrantov-za-narusheniya)

Literaturverzeichnis:

- Abaschin, S. (2014): Движения из Центральной Азии в Россию: в модели нового мироустройства [„Bewegungen von Zentralasien nach Russland: Ein Modell für eine neue Weltordnung“], abrufbar unter: https://eusp.org/sites/default/files/archive/et_dep/abashin/ProEtContra_62_73-83.pdf, letzter Zugriff: 19.08.2024.

- Current Time (2022, 24. Jan.): „Левада“: лишь 4% россиян согласны, чтобы выходцы из Центральной Азии были членами их семьи, а четверть предлагают не пускать их в Россию [„,Levadaʻ: Nur vier Prozent der Russen sind der Meinung, dass Zentralasiaten zu ihrer Familie gehören sollten, während ein Viertel vorschlägt, dass sie nicht nach Russland einreisen dürfen“], abrufbar unter: https://www.currenttime.tv/a/russia-migranty/31668927.html, letzter Zugriff: 19.08.2024.

- Government.ru (2016, 5. Apr.): Президент России подписал указ о передаче функций Госнаркоконтроля и миграционной службы в систему МВД России [„Russlands Präsident unterzeichnete einen Erlass über die Übertragung der Funktionen des staatlichen Drogenkontrolldienstes und des Migrationsdienstes auf das russische Innenministerium“], abrufbar unter: http://government.ru/info/29868/, letzter Zugriff: 19.08.2024.

- Gusewa, M. (2023, 1. Febr.): Как вторжение в Украину изменило миграцию в Россию и экономику стран Центральной Азии. Дата-исследование Настоящего Времени [„Wie der Einmarsch in die Ukraine die Migration nach Russland und die Wirtschaft in Zentralasien veränderte. Datenrecherche von Current Time“], abrufbar unter: https://www.currenttime.tv/a/data-story-migration-ru-ca/32247915.html, letzter Zugriff: 19.08.2024.

- Iwachnjuk, I. (2023, 17. Nov.): Трудовая миграция в Россию: взгляд через призму политических, экономических и демографических тенденций [„Arbeitsmigration nach Russland: Ein Blick durch das Prisma politischer, wirtschaftlicher und demografischer Trends“], abrufbar unter: https://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/analytics/trudovaya-migratsiya-v-rossiyu-vzglyad-cherez-prizmu-politicheskikh-ekonomicheskikh-i-demografichesk/?sphrase_id=150081648, letzter Zugriff: 19.08.2024.

- Schukurow, A. (2023, 22. Dez.): В 2023 году приток мигрантов в Россию упал до минимальных значений [„Im Jahr 2023 sank der Zustrom von Migranten nach Russland auf seinen niedrigsten Wert“], abrufbar unter: https://tochno.st/materials/v-2023-godu-pritok-migrantov-v-rossiiu-upal-do-minimalnyx-znacenii-eto-mozet-stat-uze-cetvertoi-volnoi-spada-migracii-s-konca-2000-x-no-poka-ona-mense-cem-ozidalos, letzter Zugriff: 19.08.2024.

12/06/2024: China’s Growing Influence in Africa: Why the European Union Can’t Keep up with China

$145.52 billion: This figure corresponds to the value of Chinese exports to African countries from 2021, with a strong upward trend (Statista 2022: 4). It’s no secret that China’s international relations are closely linked to China’s economic growth and strength. Since the 1950s, China has used this power, inter alia, to gain a foothold in Africa. By means of extensive infrastructure projects and investments in the African economic sector, Beijing is gradually expanding its influence on the African continent. Hailed by many African countries, whereas eyed with suspicion by European countries, China’s ‘African conquest’ is attracting much international attention. China’s influence is growing at a rapid pace, and not just in the economic sphere. Meanwhile, it becomes increasingly difficult for the European Union to counteract this situation since the EU is being pushed out of Africa. Chinese economic support seems to be a widespread phenomenon in African states. 63 per cent of African countries assess China’s influence basically positive, while only 14 per cent consider it rather negative (Statista 2022: 43). These numbers differ a lot from those of European member states. Based on these observations, the question that naturally arises is, why is that? Is Europe no longer popular in Africa? Do European deals, relations and supports have not the same quality as China’s? Or to put it in a more scholarly way: how come China’s efforts manage to enjoy greater popularity in Africa than those of the European Union? Why can European economic relations not keep up with China’s? The following article is intended to give the decisive reasons for this.

A first difference and a possible reason why African states view the relations with the European Union differently or more negatively than with China lies in the past historical relations between the various actors. The international relations between member states of the European Union and Africa are shaped by the time and the effects of the colonial era. Undeniably, there is a strong bond between these two continents, whether positive or negative. Based on the fact that European colonial powers have been active in Africa for centuries, one should assume that these powers would have learned from their previous mistakes and gained some understanding of their African neighbours through time and the exchange of culture, ideas and values which should help them gain a decisive advantage over China’s efforts.

However, various agreements between what was then the European Community and the African developing countries exemplify that this was not the case. Treaties such as the Yaoundé Convention (1963), the subsequent Lomé Convention (1975) or the Cotonou Partnership Agreement (2000) were agreements intended to promote development and economic growth in said countries. One thing that all agreements had in common was that the beneficiaries of these agreements were almost exclusively the European states (Barton & Men 2011: 5f.). Despite the partial support that these agreements nevertheless provided for African states, post-colonial relations continued to be characterized by asymmetry – a circumstance that lasted until the 1990s and which is presumably still very much anchored in the memory of Africa’s political and economic elite. Therefore, it is all the more interesting to observe how the rhetorical reorientation in the relations between the European and African states took place in the 2000s. Relating thereto, the Joint Africa-EU Strategy (JAES) from 2007 deserves a special mention. This new initiative represents a partnership on an equal footing and is equally beneficial for both sides. How can this change of direction be explained? It is likely that China’s influence at this point had reached a level that the European Union was now aware of as a potential threat.

China has maintained friendly and supportive relations with various African countries since the 1950s. A factor that has supported this circumstance is certainly the mutual experience of foreign colonial rule. China quickly managed to gain a foothold in Africa through bilateral relations with various African countries. Where former European colonial powers tried to defend their dwindling influence by interfering in the domestic affairs of their former (now independent) colonies, China managed to build long-term and mutually respectful relationships with African countries by supporting independence movements and development aid. In the second half of the 20th century, China developed itself from being an altruistic financier and supporter (both politically and economically) to becoming Africa’s trading partner while always recognizing this as a partnership on equal terms. Just around the turn of the millennium, China’s growing influence had reached an internationally competitive level capable of challenging Europe’s position on the African continent.

Another aspect of economic relations that should not be underestimated and which may be the reason why China has so quickly caught up and overtaken the European countries in the race for influence on the African continent is that Sino-African relations are not tied to politically fulfilled conditions. The European states are trying to combine their economic interests with political development and Western ideals. The establishment of democracy and the protection of human rights are elementary components of the economic agreements. In contrast, the Chinese approach is completely value-free. Linked to this demeanour is one of the most important principles in China’s Africa policy, namely state sovereignty. Accordingly, a change in governance towards democracy, which is a domestic governance issue, would violate this principle. The Democracy Index for 2022 shows that the majority of African states are still authoritarian or hybrid regimes, which leads to the unfortunate circumstance that economic agreements and development aid in these countries are proving to be difficult or slow for EU states (EIU 2022). While European economic and development policy is restrained due to these hurdles, Chinese companies have no problem getting fully involved and becoming active. Especially on a continent where authoritarian and hybrid systems are dominant, this Chinese approach is well received, at least by the leaders and elites of African countries. Although the European value-based policy is recognized by many states, it is often interpreted as patronizing (Shikwati et al. 2022). It seems that the very ideals and values that the European Union and its member states promote are at a distinct disadvantage in Africa politics, and therefore in the race for influence.

Another final point is the speed and efficiency with which China is making its economic investments and moving forward with its infrastructure projects. The study by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation, cited above, shows that the majority of African people surveyed feels that China is much faster in making decisions about possible investments and in completing various infrastructure projects (Shikwati et al. 2022). While in European countries such projects have to pass through a complex process (evaluation, discussion on supranational and national level, tender procedure, approval) and the slow-grinding wheels of bureaucracy, China is already implementing one project after another. Why is that? This question can be answered relatively easy. On the one hand, China solely represents itself and its interests, the Union, on the other hand, is somehow trying to create a uniform Africa policy and a compromise between the 27 member states. But compromises take time – time the EU does not have if it wants to keep up with China’s pace. Another reason why the EU is lagging behind in pace and efficiency is the type of governance. After all, democratic processes need time, as different opinions and views have to be considered and heard, and interests have to be formed. The authoritarian government based in Beijing, on the other hand, is not ‘biased’ by these time-consuming democratic processes. China is an authoritarian state. There are clear guidelines from the Chinese state that set out the route for Chinese officials and Chinese companies operating in Africa. Principles and rules that have existed and been adapted for decades, when China took the step from altruistic friend and supporter to trading partner on an equal footing in the 1970s (Barton & Men 2011: 7).

In conclusion, several reasons emerge to explain why China’s influence is growing so rapidly and why ‘Chinese efforts’ are valued more highly than European ones by elites and leaders in African countries. On the one hand, the difficult colonial past of Europe and Africa plays a crucial role, especially in connection with past economic agreements and the associated development aid. European countries have historically designed these agreements and treaties asymmetrically in their favour – agreements that were perhaps not only of great economic importance for countries shaken by colonialism, but perhaps also had symbolic value due to past colonial experiences. On the other hand, the offer of economic cooperation on the terms of democracy and human rights does not appear to be lucrative for many African states, which could have something to do with their own way of governing. Furthermore, one must ask the question why an authoritarian or hybrid state would agree to the EU’s offer when it can get the same level of economic cooperation or investment from China without having to seek any domestic political efforts to promote democracy or uphold human rights. Last but not least, China acts faster than the EU.

What does that mean for the future? It can be assumed that China’s growing influence will continue to grow, not only economically but also politically. The first signs of how great China’s influence already is can be seen in the opinions of African states on the Taiwan question and in the steadily expanding range of security policy measures that China is implementing in Africa. In this regard, African countries are facing a dubious future. On the one hand, they are becoming heavily dependent on the People’s Republic of China as a result of the investments and loans from Chinese investors. This ‘debt trap’ can have negative effects in the long term, and African states could become vulnerable to political blackmail. On the other hand, the African countries are benefiting from China’s aggressive actions since the European countries are now forced to counteract this advance if they do not want to lose their influence in Africa completely – a scenario the EU states cannot actually afford due to the wealth and diversity of resources Africa has to offer. The future on how the race for Africa and the clash between two global players on the African continent will play out, remains something to look out for.

(Hinweis: Der vorliegende Blog-Beitrag gibt nicht zwingend die Meinung des KFIBS e. V. wieder.)

(Bildnachweis für Beitragsbild: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/ausland/china-afrika-forum-das-experimentierfeld-fuer-chinas-aussenpolitik-15768665.html)

Bibliography:

- Barton, Benjamin & Men, Jing (2011): China and the European Union in Africa: Partners or Competitors? Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- EIU – Economist Intelligence (2022): Democracy Index 2022, available at https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2022/ (last access: 12 June 2024).

- Shikwati, James/Adero, Nashon & Juma, Josephat (2022): The Clash of Systems? African Perceptions of the European Union and China Engagement, Policy Paper, June 2022, Friedrich Naumann Foundation, available at: https://www.freiheit.org/de/ostafrika/clash-systems-african-perceptions-european-union-and-china-engagement (last access: 12 June 2024).

- Statista (2022): Africa-China Relations, Statistics Report, available at: https://www.statista.com/study/102562/africa-china-relations/ (last access: 12 June 2024).

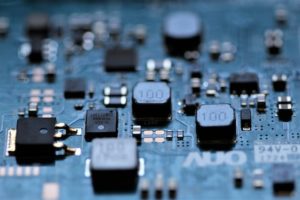

05/12/2022: Towards a European ‘Open Strategic Autonomy’: A German View on the ‘European Chips Act’

Undoubtedly, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has radically changed the headlines of European newspapers this year. Unlike before, issues of security policy are suddenly at the centre of media attention. Moreover, the far-reaching financial consequences of the war, for example shortages in the energy supply, are painfully felt by the broader population in European economies.

Behind the scenes there is, however, another power struggle in existence which may affect the course of European economies in the coming decades. The increasing digital automation of global industries has resulted in a soaring demand for semi-conductors. The damage caused by a shortage in the global semi-conductor supply could be observed by its effect on the German car industry in 2022.

The European Commission expects the Chip demand to double between 2022 and 2030 as indicated in the recently published ‘European Chips Survey’. Semi-conductors are the key component of the increasing global digitalisation process. This in turn causes an extreme global dependency which can be instrumentalised by certain regimes in the context of geopolitical power struggles.

So far, however, no country can produce semi-conductors autonomously. The production of wavers is a highly integrated process, and the semi-conductor value chain depends on a few actors which in turn are highly dependent on each other. However, the rising power ambition of China and the growing tensions with Taiwan raise serious concerns regarding the stability of this system of interconnected and international trade in the future. Thanks to leading global players in the semi-conductor value chain, such as TSMC, Taiwan so far can uphold its often cited ‘Silicon Shield’. The consequences of an attack on Taiwan by China for the global semi-conductor value chain would thus be devastating.

Following the EU’s leitmotif in the new trade policy of ‘Open Strategic Autonomy’, the EU has to balance the often contradictory concepts of economic openness on the one hand and strategic autonomy on the other hand. From this perspective, the ‘European Chips Act’ can be interpreted as an attempt by the European Commission to secure the resilience and competitiveness of European economies in the future. According to official EU estimates, of one trillion microchips manufactured around the world in 2020, the EU had a share of 10 per cent of the global microchips market. The ambitious goal of the so-called European Chips Act is to increase this share to 20 per cent of the global market until the end of this decade. Since the global market size for semi-conductors will also double until 2030, this would mean an increase by the factor five. Therefore, this goal is most likely not realisable as private sector actors like the association of Germany’s Electro and Digital Industry (ZVEI e.V.) indicate. However, the USA with the so-called CHIPS for America Act and, most notably, China with the ‘14th Five-Year Plan’ are trying to strengthen their semi-conductor industries as well.

The necessary size of the ‘European Chips Act’ and which waver size should be targeted in the production is still an ongoing political dispute.

Interestingly, however, there seems to be a broad agreement of many relevant actors on another issue. In their public statements both private sector actors like the association of Germany’s Electro and Digital Industry (ZVEI e.V.), the high-tech network Silicon Saxony e.V., the DIHK, as well as public actors like the German Federal Foreign Office or the European Commission state that the production of semi-conductors and their geopolitical consequences exceed both politically and financially the capabilities of the single European nation state. In contrast to the seemingly everlasting EU-bashing and unconstructive anti-EU rhetoric from some European leaders such as, most notably, Viktor Orbán, the European project seems to be more than a loose political association based on an outdated peace-building ideology of the 20th century. On the contrary, the European project presents itself in the 21st century not as a naïve dream but as a geopolitical necessity if European nation states want to omit the strategical dependence of global powers in a multilateral world order.

To refer to an unfortunate term, most famously coined by the former chancellor Angela Merkel: In the long run, a European agreement is ‘alternativlos’ or, in other words, without any reasonable alternative.

(Hinweis: Der vorliegende Blog-Beitrag gibt nicht zwingend die Meinung des KFIBS e. V. wieder.)

(Bildnachweis für Beitragsbild: Photo by Anne Nygård on Unsplash)

17.03.2022: Zum derzeitigen Verhandlungsstand im Ukraine-Krieg: Nur wenig Hoffnung auf eine diplomatische Lösung

Alle Seiten im Hinblick auf den russischen Angriffskrieg betonen immer wieder, dass eine Konfliktlösung nur über eine Vereinbarung zwischen den unmittelbar involvierten Parteien zu finden sein wird. Seit einigen Tagen gibt es dazu entweder direkte Treffen zwischen Vertretern der Ukraine und Russlands oder Verhandlungsrunden im Beisein eines Mediators oder eines Moderators. Im letzten Fall haben sich beispielsweise die Türkei und Israel, die gute Beziehungen zu beiden Konfliktparteien pflegen, ins Spiel gebracht. Bisher sind jedoch die Forderungen von russischer Seite, die eine Anerkennung der Krim als Teil Russlands oder die Anerkennung der ostukrainischen Separatistengebiete im Donbass als unabhängige Staaten beinhalten, für die Ukraine inakzeptabel. Hinzu kommen Forderungen nach einem neutralen Status der Ukraine und einer „Entmilitarisierung“ des Landes, bei denen es mehr Verhandlungsspielraum zu geben scheint. Die Ukraine dringt ihrerseits hingegen auf ein Ende des Krieges mit einem vollständigen Abzug der russischen Truppen sowie auf verlässliche und überprüfbare Sicherheitsgarantien im Anschluss daran. Ein Großteil der Verhandlungen bezieht sich außerdem auf humanitäre Korridore für die belagerten ukrainischen Städte, die eine Evakuierung und Versorgung der Zivilbevölkerung oder einen Austausch von Gefangenen ermöglichen sollen. Es zeigt sich aber auch, dass selbst bereits getroffene Vereinbarungen nicht eingehalten werden, da seit Tagen festgeschriebene Routen teilweise oder gar ganz blockiert werden. Beide Konfliktparteien geben sich dafür gegenseitig die Schuld.

Aus einer theoretischen Perspektive werden die aktuellen Verhandlungen noch nicht zu einer diplomatischen Lösung führen. Weder für die ukrainische noch für die russische Seite sind die materiellen und immateriellen Kosten des Konfliktes derzeit hoch genug, um von Positionen abzurücken, die von der jeweils anderen Seite nicht akzeptabel sind oder selbst genügend Zugeständnisse zu machen, um eine diplomatische Einigung zu erzielen. Es hat sich bisher auch noch keine Pattsituation ergeben. Beide Seiten – insbesondere die russische Seite – hoffen darauf, dass die Kosten des Konfliktes sich zuungunsten der jeweils anderen Seite entwickeln werden. Die zunehmend bewusste Bombardierung der ukrainischen Zivilbevölkerung ist u. a. ein Druckmittel gegenüber der politischen Führung in Kiew, um diese zu Zugeständnissen zu bringen, sodass das Leid der eigenen Bevölkerung gelindert wird. Es ist daher richtig und wichtig, den politischen und wirtschaftlichen Druck auf die Russische Föderation zu erhöhen und gleichzeitig die Ukraine bestmöglich zu entlasten, um so Moskau von seinen Maximalforderungen abzubringen und doch noch eine Verhandlungslösung zu ermöglichen. Eine Konfliktlösung ist in dem Moment greifbar, in dem die Präsidenten der Ukraine und Russlands direkt miteinander sprechen und verhandeln, was zwar wiederholt vom ukrainischen Präsidenten Wolodymyr Selenskyj gefordert wurde, bislang jedoch von russischer Seite unerwidert geblieben ist. Dazu wird es aller Voraussicht nach erst kommen, wenn die beiden Delegationen in den Vorverhandlungen eine solide Grundlage für eine Vereinbarung gefunden haben.

(Hinweis: Der vorliegende Blog-Beitrag gibt nicht zwingend die Meinung des KFIBS e. V. wieder.)

(Bildnachweis für Beitragsbild: Photo by ev on Unsplash)

15.03.2022: Der Ukraine-Krieg vor dem Hintergrund zweier gängiger politikwissenschaftlicher Friedensbegriffe

Der Angriffskrieg Russlands auf die Ukraine hat die Friedenszeit in Europa beendet. Die unmittelbaren Opfer sind unbestreitbar die Menschen in der Ukraine selbst – und es bleibt nur zu hoffen, dass die Kampfhandlungen möglichst schnell beendet werden. Diesbezüglich wird immer häufiger die Frage in den Raum gestellt, ob es für den Frieden nicht dienlicher wäre, wenn sich die Menschen in der Ukraine einfach ergeben würden. Doch wäre das Resultat nicht vielmehr mit einer repressiven Besatzung als eine Art von Frieden gleichzusetzen? Welcher Frieden soll genau entstehen? Und welche Form des Friedens ist unter den aktuellen Umständen die wahrscheinlichste?

In der Politikwissenschaft wird zwischen „positivem“ und „negativem“ Frieden unterschieden. Das Konzept des „positiven“ Friedens verkörpert fundamentale Grundwerte wie Gerechtigkeit und Freiheit. Es beschreibt einen Zustand, der sowohl personelle Gewalt (Krieg) als auch strukturelle Gewalt (Formen der Diskriminierung und Benachteiligung) ausschließt. Diese Art des Friedens ist zurzeit jedoch äußerst unrealistisch. Die Voraussetzung für die Verwirklichung eines „positiven“ Friedens ist zunächst einmal die Realisierung eines „negativen“ Friedens, unter welchem die Abwesenheit von Krieg zu verstehen ist. Die obersten Prioritäten des „negativen“ Friedens sind daher eine Deeskalation bestehender Konflikte und die Beendigung militärischer Gewaltanwendung. Ein „negativer“ Frieden in Form einer Waffenruhe, eines einfachen Waffenstillstands zwischen Russland und der Ukraine, wäre ein erster Schritt in die richtige Richtung, da dies die Grundlage für ein mögliches Friedensabkommen zwischen den beiden Kriegsparteien legen würde.

Von Kimberly Schmidt

(Hinweis: Der vorliegende Blog-Beitrag gibt nicht zwingend die Meinung des KFIBS e. V. wieder.)

(Bildnachweis für Beitragsbild: Photo by Elena Mozhvilo on Unsplash)