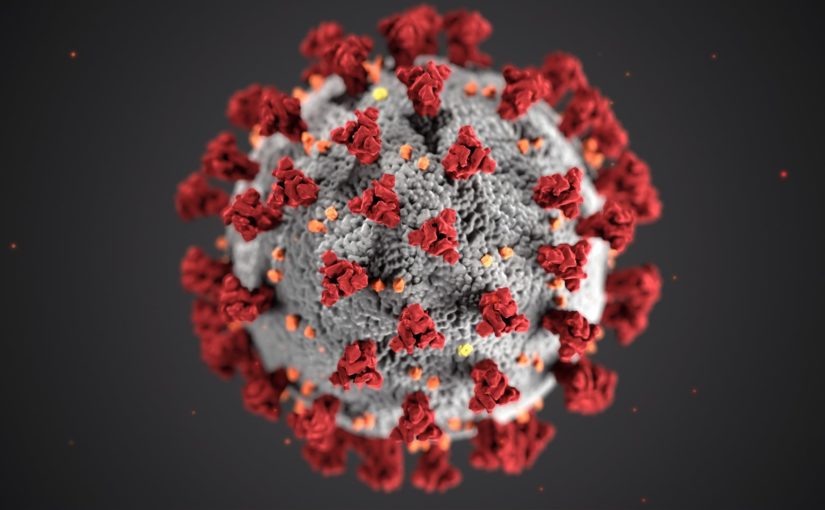

For this article we talked to both women and men from Uganda, Zambia, Tanzania and South Africa.* It aims to show the width in which girls and women are affected during the COVID-19 pandemic and how this relates to gender. Based on how the people we talked to – mostly good friends and old acquaintances – perceive the situation around them, the article touches upon aspects that apply globally in similar ways. However, the focus lies on how women (and girls) feel the effects differently due to the particular circumstances and lockdown measures in their countries. For example, the ban of public transportation with little private car, motorbike or bicycle ownership, the criminalization of sex work and other economic structures embedded in weak social security systems, the tabooization of sex education and teenage pregnancies, and gender norms in general. While the challenges are saddening, there is hope for new windows of opportunity to keep the fight for gender equality going. Yes, it is indeed complex, but people can learn to understand part of the struggle, especially those who have not experienced it themselves.

*Photos, names and titles were used according to their own wishes.

* * *

At Home: Care Work and Gender-Based Violence

Generally speaking, women are affected differently by the pandemic than men in several ways. Needless to say, in many countries in the world the amount of care work, mostly performed by women, has increased with schools being closed and kids staying home. Yet, there are many facets to how people experience such changes.  Leah Mushi, a journalist from Tanzania, describes how “increased pressure for working women to deliver at work and again to fulfill […] duties at home […] can cause stress and anxiety”. In her view “men don’t do the same […], some help their families but again, they are not expected to do it every day”. Mwansa Mungela from Zambia, on the other hand, shares how similar pressure can be felt as a man.

Leah Mushi, a journalist from Tanzania, describes how “increased pressure for working women to deliver at work and again to fulfill […] duties at home […] can cause stress and anxiety”. In her view “men don’t do the same […], some help their families but again, they are not expected to do it every day”. Mwansa Mungela from Zambia, on the other hand, shares how similar pressure can be felt as a man.

“For Zambia […], men are culturally considered to be stronger than women. Hence during the days of quarantine, men have largely been expected to go out and do the shopping or any other tasks outside the home […]. One cashier in Shoprite [a big chain store company] told me that during the days of quarantine it is men who were seen shopping more.” – Mwansa Mungela, Zambia

“For Zambia […], men are culturally considered to be stronger than women. Hence during the days of quarantine, men have largely been expected to go out and do the shopping or any other tasks outside the home […]. One cashier in Shoprite [a big chain store company] told me that during the days of quarantine it is men who were seen shopping more.” – Mwansa Mungela, Zambia

In addition, he sees a higher financial burden falling on men as ‘heads of the house’, since they are more often employed than women and generally earn more, whereas women “are considered as caregivers hence they stay home with the children”. This, however, clearly also underlines gender inequality in terms of lower economic opportunities and gender pay gaps that have existed for many years before the COVID-19 outbreak. Furthermore, it leaves the situation of single mothers or female-run households unaddressed.  To that Percival Quina from South Africa adds: “In rural communities so many households are run by women. They are the breadwinners of the family. The socio-economic impact of COVID-19 is devastating to these female-run households.” He states: “Last week [19th April 2020] I saw an interesting statistic released by the National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD) that 54.7% of the infected are female (male – 44.8%). […] Although this isn’t a big difference, it is quite interesting given that so many women in South Africa perform home-based care work.” – Percival Quina, South Africa

To that Percival Quina from South Africa adds: “In rural communities so many households are run by women. They are the breadwinners of the family. The socio-economic impact of COVID-19 is devastating to these female-run households.” He states: “Last week [19th April 2020] I saw an interesting statistic released by the National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD) that 54.7% of the infected are female (male – 44.8%). […] Although this isn’t a big difference, it is quite interesting given that so many women in South Africa perform home-based care work.” – Percival Quina, South Africa

These numbers oppose Mwansa’s initial impression from Zambia that there might be a link between women staying at home and a reduced risk of infection. A study about Ebola has shown that there is moreover reason to worry about the increased risk and incidences of domestic violence, both against women and children. Mwansa adds to this perspective that “the surge in cases of Gender-Based Violence (GBV) that was recently reported by […] a local [Zambian] NGO, could be attributed to the economic and social stress that has been brought upon men (being the common GBV perpetrators) by the restrictions on movements”. This can neither serve as an excuse nor as an explanation for violence against women and girls. It rather shows the unequal distribution of power which needs to be addressed. Furthermore, Maria Alesi, a feminist from Uganda, highlights that women face increased sexual harassment and exploitation also outside their own household with some men asking for sex in exchange for food. Women were also an easy target for police brutality when selling food in the streets to make a living at the beginning of the lockdown when food relief was not yet available. Although men feel the violence stemming from the militarization of the lockdown process too, which goes to the extent of people claiming that it has killed more people than COVID-19, there is another aspect coming in for women as Maria explains: “Work initially took women out of the private sphere into the public. This process is now reversing, and women are pushed back to staying at home, thereby losing opportunities for income generation and independence.”

The Less Visible: Teenage Pregnancies and Sex Work

There are also less visible forms of how lockdown measures hit women and girls harder than men and boys. Firstly, sex workers, for instance, are criminalized in many countries. In Uganda, they struggled to claim food distributed by the Government to people whose income was affected by the lockdown, because sex work is illegal. Aside from losing income, sex workers in Uganda are also at risk of contracting the virus, given that many cross-border cargo truck drivers, who make up a significant portion of their clients, have tested positive for it. Due to these circumstances, “sex workers in some border districts were thrown out of their houses […], and there have been cases of arbitrary arrests”, Maria reports. Secondly, different stories suggest that teenage pregnancies are on the rise. Although teenage pregnancies cannot exclusively be attributed to coronavirus lockdowns, a rise in numbers could possibly be explained by girls lacking protection from increased risk of sexual abuse when staying at home and schools being closed as well as by aggravated access to contraceptives and sex education. In Uganda, NBS reports that pregnant girls are expected to miss school next term. In Tanzania, it is even ruled by law that pregnant girls may not go back to school at all. Considering that only a few girls might generally be able to afford or find someone to take care of the baby and continue with their education, the impact of pregnancy and raising a child might be much greater for the majority of them with regard to their socio-economic and educational status than one missed school term.

Multiple Crises: Health, Economic and Governance Issues – the Example of Uganda

“Poverty is feminized and the face of poverty is women.” – Maria Alesi, Uganda

In many African and also non-African countries, challenges in connection to the coronavirus cannot be seen independently from other concerning issues like underfunded health systems, lacking social protection and climate change. In addition to the pandemic, some consequences of climate change, namely flooding, mudslides and a surge in natural disasters exacerbate socio-economic conditions. Maria alerts that Lake Victoria is at its highest water level ever. COVID-19, thus, intensifies the problems that people have been facing now and before the pandemic. This again affects women in particular ways. Regarding health, Maria elaborates how the majority of frontline workers in the fight against COVID-19 are women. Also across the globe, nurses are mainly female. Maria, additionally, narrates how at the beginning of the lockdown, which included a ban on public transportation, pregnant women due to give birth died on their way to the hospital because of lacking transport and unreasonable implementation of the given directives. Economically, Maria sees several female dominated sectors like flower farms, cloth manufacturing, housekeeping, and services in restaurants and hotels like cleaning, etc. to be affected. She describes how in a bid to provide for physical distancing, some people had to leave the markets and only food vendors were allowed to stay. This disproportionately affected women since they make up the majority of market vendors. Those who stayed were, furthermore, asked to sleep in the markets to reduce unnecessary travel, a directive which again raises health and safety concerns. She adds that when jobs are lost, more women tend to get laid off, even though trade unions try to fight for reduced working hours, shifts and pay rations to adjust to economic difficulties arising from containing the pandemic. In the education sector, school enrollment and attendance of girls especially may drop post-pandemic due to increased poverty rates from the above-mentioned economic difficulties, teenage pregnancies and need for extra supportApart from reduced interest rates implemented by the Bank of Uganda to make loans cheaper, not much has been done in providing the necessary economic stimulus packages for recovery, and the recently announced national budget sounds to Maria “as if we didn’t have a lockdown”. Hopes for more money getting allocated to the social sectors stay unfulfilled and the question of how to deal with an increased debt burden remains. Maria thinks that governments often look at short-term results, hence a long-term improvement in quantity and quality of education, for example, might still take a while.

Hope for Opportunities and Outlook

On the downside, multiple burdens make the mobilization of women to fight for their rights more difficult. On the upside, Maria believes that this can be “a great time for women to rethink the work that they bring into the space”. The coronavirus increases vulnerabilities, but instead of focusing on COVID-19 alone we should look at tackling important political issues in a joint manner. The current global pandemic reminds us once more to rethink how gender roles and norms are distributed and how equal opportunities benefit the common good of societies. It emphasizes the need to address gender inequalities, both in the specific ways as it unfolds regionally and in the shared struggle worldwide.

This article was written by Verena G. Himmelreich with the active support of Miriam Kalkum, Sandra M. Dürr, Lennart P. Groscurth, Alena Sander and Samantha Ruppel.

(Hinweis: Der vorliegende Blog-Beitrag gibt nicht zwingend die Meinung des KFIBS e. V. wieder.)